Difference between revisions of "Mupen64plus dynamic recompiler"

(→Self-modifying code detection) |

(→Compile options) |

||

| Line 289: | Line 289: | ||

If this is defined, the UXTH instruction is not used, and the dynamic recompiler will generate literal pools instead of using movw/movt. This provides compatibility with older processors, but generates somewhat less efficient code. | If this is defined, the UXTH instruction is not used, and the dynamic recompiler will generate literal pools instead of using movw/movt. This provides compatibility with older processors, but generates somewhat less efficient code. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === RAM_OFFSET === | ||

| + | |||

| + | When compiling for ARM, this allocates an additional register which is used to add an offset to all pointers to memory addresses between 0x80000000 and 0x807FFFFF. This allows the N64's memory to be mapped at an alternate address. This incurs a small performance penalty, but is required for certain operating systems (eg Google Android, which places shared libraries at 0x80000000). | ||

| + | |||

| + | This option is not used for x86. The x86 instruction set allows for a full 32-bit offset in the instruction encoding, making it unnecessary to allocate an additional register for this purpose. | ||

=== CORTEX_A8_BRANCH_PREDICTION_HACK === | === CORTEX_A8_BRANCH_PREDICTION_HACK === | ||

Revision as of 21:50, 2 February 2011

This page describes the dynamic recompiler in Mupen64Plus, and the changes made for the ARM port.

Contents

- 1 The original dynamic recompiler by Hacktarux

- 2 Problems with the original design

- 3 A new approach

- 4 Pass 1: Disassembly

- 5 Pass 2: Liveness analysis

- 6 Pass 3: Register allocation

- 7 Pass 4: Free unused registers

- 8 Pass 5: Pre-allocate registers

- 9 Pass 6: Optimize clean/dirty state

- 10 Pass 7: Identify where registers are assumed to be 32-bit

- 11 Pass 8: Assembly

- 12 Linker

- 13 Memory manager

- 14 Invalidation and restoration

- 15 Dynamic linker

- 16 Address lookup

- 17 Cycle counting

- 18 Interrupt handler

- 19 Delay slots

- 20 Constant propagation

- 21 Translation lookaside buffer emulation

- 22 Page fault emulation

- 23 Mapping executable pages

- 24 Self-modifying code detection

- 25 Compile options

- 26 Debugging

- 27 Potential improvements

The original dynamic recompiler by Hacktarux

The dynamic recompiler used in Mupen64plus v1.5 is based on the original written by Hacktarux in 2002.

It recompiles contiguous blocks of MIPS instructions. First, each instruction is decoded into a dynamically-allocated 132-byte data structure.

typedef struct _precomp_instr

{

void (*ops)();

union

{

struct

{

long long int *rs;

long long int *rt;

short immediate;

} i;

struct

{

unsigned int inst_index;

} j;

struct

{

long long int *rs;

long long int *rt;

long long int *rd;

unsigned char sa;

unsigned char nrd;

} r;

struct

{

unsigned char base;

unsigned char ft;

short offset;

} lf;

struct

{

unsigned char ft;

unsigned char fs;

unsigned char fd;

} cf;

} f;

unsigned int addr; /* word-aligned instruction address in r4300 address space */

unsigned int local_addr; /* byte offset to start of corresponding x86_64 instructions, from start of code block */

reg_cache_struct reg_cache_infos;

} precomp_instr;

The decoded instructions are then compiled, generating x86 instructions for each MIPS instruction. A 32K block is allocated with malloc() to hold the x86 code. If this size proves insufficient, it is incrementally resized with realloc().

MIPS registers are allocated to x86 registers with a least-recently-used replacement policy. All cached registers are written back prior to a branch, or a memory read or write.

To facilitate invalidation and replacement of modified code blocks, each 4K page is compiled separately. If a sequence of instructions crosses a 4K page boundary, the current block is ended, and the next instructions will be compiled as a separate block.

Branch instructions within a 4K page are compiled as branches directly to the target address. Branches which cross a 4K page go through an indirect address lookup.

Compiled code blocks are invalidated on write. On an actual MIPS CPU, the instruction cache is invalidated using the CACHE instruction, however a few N64 games clear the cache using other methods. Trapping writes appears to be the most reliable method of ensuring cache coherency in the emulated system. The cache instruction is ignored.

Problems with the original design

The most significant performance problem with this design is its excessive memory usage. The decoded instruction data is retained (132 bytes for each MIPS instruction) and occasionally referenced during execution. Memory accesses frequently miss the L2 cache, resulting in poor performance.

Additionally, the register cache is relatively inefficient, since all registers are flushed before any read or write operation.

A new approach

To reduce memory usage, the new design allocates a single large block of memory (currently 16 MiB) which is used for recompiled code. This memory is allocated using mmap with the PROT_EXEC bit set, to ensure operation on CPUs with no-execute (NX) page permissions.

Contiguous blocks of MIPS instructions are compiled (that is, it does not attempt to follow branches or 'hot-paths').

The recompiler consists of eight stages, plus a linker, and a memory manager.

Compiled blocks are invalidated on write, as before, however as the compiler will cross a 4K page, writes may invalidate adjacent pages as well.

Currently the dynarec generates x86, x86-64, ARMv5, and ARMv7 (little-endian). Most of the code is shared between the architectures, but a different code generator is included at compile time, using different #include statements depending on the CPU type.

Pass 1: Disassembly

When an instruction address is encountered which has not been compiled, the function new_recompile_block is called, with the (virtual) address of the target instruction as its sole parameter. If the address is invalid, the function returns a nonzero value and the caller is responsible for handling the pagefault.

Instructions are decoded until an unconditional jump, usually a return, is encountered. Disassembly is ordinarilly continued past a JAL (subroutine call) instruction, however this strategy is abandoned if invalid instructions are encountered.

Up to 4096 instructions (16K of MIPS code) may be disassembled at once. Surprisingly, some games do actually reach this limit.

Pass 2: Liveness analysis

After disassembly, liveness analysis is performed on the registers. This determines when a particular register will no longer be used, and thus can be removed from the register cache.

A separate analysis is done on the upper 32 bits of 64-bit registers. This can determine when only the lower 32 bits of a register are significant, thus allowing use of a 32-bit register. This enables more efficient code generation on 32-bit processors.

Pass 3: Register allocation

The 31 MIPS registers must be mapped onto seven available registers on x86, or twelve available registers on ARM.

Instructions with 64-bit results require two registers on 32-bit host processors. 32-bit instructions require only one. A flag is set for registers containing 32-bit values, and these registers will be sign-extended before they are written to the register file.

Registers are made available using a least-soon-needed replacement policy. When the register cache is full, and no registers can be eliminated using the liveness analysis, a ten-instruction lookahead is used to determine which registers will not be needed soon and these registers are evicted from the cache.

Pass 4: Free unused registers

After the initial register allocation, the allocations are reviewed to determine if any registers remain allocated longer than necessary. These are then removed from the register cache. This avoids having to write back a large number of registers just before a branch, and makes more registers available for the next pass.

Pass 5: Pre-allocate registers

If a register will be used soon and needs to be loaded, try to load it early if the register is available. This improves execution on CPUs with a load-use penalty.

Pass 6: Optimize clean/dirty state

If a cached register is 'dirty' and needs to be written out, try to do so as soon as the register will no longer be modified. This avoids having to write the same register on multiple code paths due to conditional branches. Additionally, try to avoid writing out dirty registers inside of loops.

Pass 7: Identify where registers are assumed to be 32-bit

When a 64-bit register is mapped to a 32-bit register with the assumption that the value will be sign-extended before being used, it is necessary to ensure that no register contains a 64-bit value when branching to such a location. These instructions are flagged to identify them as requiring 32-bit inputs. This information is used by the linker, and the exception return (ERET) handler.

Pass 8: Assembly

This generates and outputs the recompiled code.

Following the main code block, handlers for certain exceptions as well as alternate entry points are added.

If a recompiled instruction relies on a certain MIPS register being cached in a certain native register, then a short 'stub' of code is generated to load the necessary registers. When an instruction outside of this block needs to jump to that location, it will instead jump to the stub. The necessary registers will be loaded, and then it will jump into the main code sequence.

On architectures which require literal pools (ARMv5) these are inserted as necessary.

Linker

The linker fills in all unresolved branches. Branches within the block are linked to their target address. Branches which jump outside of the block are linked to their target if that address has been compiled already. These inter-block branches are recorded in the jump_out array. This information will be used to remove the links in the event that the target of the branch is invalidated.

Unresolved branches point to a stub which loads the address of the branch instruction and the virtual address of its target into registers, and calls the dynamic linker. When this code is executed, the dynamic linker will compile the target if necessary, and then patch the branch instruction with the new address.

Memory manager

The last step in new_recompile_block is to ensure that there will be sufficient memory available to compile the next block. If there is not, then the oldest blocks are purged.

The dynarec cache can be described as a 16MB circular buffer divided into eight segments. Memory is allocated in order from beginning to end.

When there are less than 2 empty segments, the next segment in sequence is cleared, wrapping around to the beginning of the buffer. This continues as memory is needed, wrapping around from end to beginning.

Invalidation and restoration

Normally, code blocks are looked up via a hash table, using the virtual address of the target instruction. However, for purposes of invalidation, blocks are grouped by physical address. This can be described as a virtually-indexed, physically-tagged (VIPT) cache.

References to compiled blocks are stored in one of 4096 linked lists in the jump_in array. Each list covers a 4K block of memory, and 2048 such lists are sufficient to cover the 8MB of RAM in the Nintendo 64. The remaining lists are for code in ROM, and the bootloader in SP memory.

When a write hits a memory page marked as cached, all entries in the corresponding list are invalidated. If any code is found to cross a 4K boundary, the adjacent lists are invalidated also.

Sometimes blocks may be invalidated even when none of the code is actually modified. This can happen if data is written to memory in the same 4K page, or if code is reloaded without actually modifying it. If blocks which were previously invalidated are subsequently found to be unmodified, those blocks are marked in the restore_candidate array. If the block remains unmodified, it will be restored as a valid block, to avoid recompiling blocks which do not need to be recompiled. This is performed by the clean_blocks function which is called periodically.

The jump_in array, which lists unmodified blocks, is physically indexed, however the jump_dirty array, which lists potentially-modified blocks, is virtually indexed. This allows blocks which have changed physical addresses, but are still at the same virtual address, to be recognized as being the same as before, and not in need of recompilation.

Dynamic linker

Branches with unresolved addresses jump to the dynamic linker. This will look through the jump_in list corresponding to the physical page containing the virtual target address. If found, the branch instruction will be patched with the address, and then it will jump to this address.

If not found, the jump_dirty list will be searched for blocks which were previously compiled but may have been modified. If a potential match is found, the code will be compared against a cached copy to determine if any changes have been made. If not, then it will jump to the block. Because the memory could be modified again, branch instructions referencing these blocks are not altered, and continue to point to the dynamic linker. These blocks will continue to be verified each time they are called, until restored to the jump_in list by the clean_blocks function described above.

If no compiled block is found, or the existing block was modified, the target is recompiled.

Address lookup

When a JR (jump register) instruction is encountered, the address of the recompiled code must be looked up using the address of the MIPS code. The majority of such instructions jump to the link register (r31) to return to the location following a JAL (call) instruction.

When a JAL or JALR is executed, the address of the following instruction is inserted into a small 32-entry hash table, which is checked when a JR r31 instruction is executed. This allows for a quick return from subroutine calls.

If the JR instruction uses a register other than r31, or the small hash table lookup fails to find a match, a larger 131072-entry hash table is checked. This table contains 65536 bins with up to 2 addresses per bin. If this also fails to find a match (which occurs less than 1% of the time) an exhaustive search of all compiled addresses within that 4K memory page is performed.

If no match is found by any of these methods, the target address is compiled, and the new address is inserted into the hash table.

Cycle counting

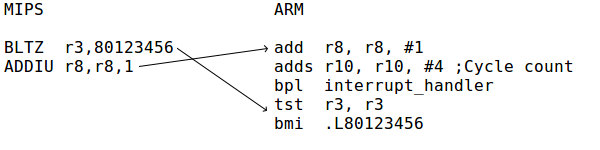

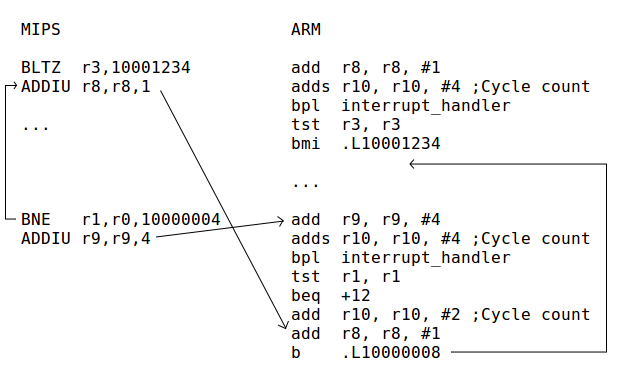

Cycles are counted before each branch by adding the cycles from the preceding instructions to a specific register. The cycle count is in R10 on ARM and ESI on x86. The value in this register is normally a negative number. When this number exceeds zero, a conditional branch is taken which jumps to an interrupt handler.

For example, the following x86 code adds eight cycles:

add $8,%esi

jns interrupt_handler

The conditional branch jumps to a small bit of code located after the main compiled block, which saves the cached registers to the register file, sets the instruction pointer which will be used upon return from the interrupt, and then calls cc_interrupt.

As in the original mupen64plus, the emulated clock runs at 37.5 MHz, and each instruction takes 2 clock cycles.

Interrupt handler

When the cycle count register reaches its limit, cc_interrupt is called, which in turn calls gen_interupt [sic]. If interrupts are not enabled, cc_interrupt returns. If interrupts are enabled, and an interrupt is to be taken, the pending_exception flag will be set. In this case, cc_interrupt does not return, and instead pops the stack and causes an unconditional jump to the address in pcaddr (usually 0x80000180).

There is one additional case where the interrupt handler may be called. If interrupts were disabled, and are enabled by writing to coprocessor 0 register 12, any pending interrupts are handled immediately.

Delay slots

MIPS has 'delay slots', where the instruction after the branch is executed before the branch is taken. Instructions in delay slots are issued out-of-order in the recompiled code.

When a branch jumps into the delay slot of another branch, this case must be handled slightly differently:

The branch test and delay slot are executed in-order if a dependency exists, or for 'likely' branches where the delay slot is nullified when the branch condition is false. These cases are infrequent (typically less than 10% of branches).

Constant propagation

When an instruction loads a constant into a register, the register is tagged as a constant. The constant tag will be retained if subsequent instructions modify the constant using other constants. During assembly, such a sequence of instructions is combined into a single load. For example:

LUI r8,12340000 --> mov $0x12345678,%eax

ORI r8,r8,5678

This optimization is not performed where a branch target intervenes, eg

...

LUI r8,12340000 --> mov $0x12340000,%eax

L1:

ORI r8,r8,5678 --> or $0x5678,%eax

...

BEQ r0,r0,L1

Registers containing constants are identified by bits in the isconst and wasconst fields of the regstat structure. The wasconst bit is set for a register if the register contained a known constant before the instruction, and the isconst bit is set for a register if the register will contain a known constant after the instruction executes.

Translation lookaside buffer emulation

Most Nintendo 64 games do not use virtual memory, but some do. At startup, main memory is directly mapped at addresses from 0x80000000 to 0x803FFFFF, or up to 0x807FFFFF if the memory expansion is used.

Normally, read or write operations are checked against this range, and if outside this range, control is passed to the appropriate I/O handler. This is done as follows:

MIPS instruction: LW r1,8(r2)

ARM code:

add r1, r2, #8

cmp r1, #8388608

bvc handler

ldr r1, [r1]

If there are valid entries in the TLB, this would instead be compiled as follows:

add r1, r2, #8

mov r0, #264

add r0, r0, r1, lsr #12

ldr r0, [r11, r0, lsl #2]

tst r0, r0

bmi handler

ldr r1, [r1, r0, lsl #2]

This looks up the offset in the memory_map table (which, in this example, is located at r11+264*4). The high bit is tested to determine whether a valid mapping exists for this page.

Page fault emulation

If a memory address references an invalid page, a conditional branch is taken to a bit of code placed after the main block. This will save any modified cached registers, and call an appropriate handler function for the address. The handler will either perform I/O, or generate an exception (pagefault).

Mapping executable pages

If the dynamic recompiler encounters code which is not in contiguous physical memory, it will end the block at the page boundary, so that the block can be removed cleanly if the mapping is changed.

There is a special case of this, where a branch and delay slot span two pages. If a branch instruction is the last instruction in a virtual memory page, it is compiled in a different manner than other branches. The branch condition is evaluated, and the target address is placed in a register (%ebp on x86, and r8 on ARM). A special form of the dynamic linker (dyna_linker_ds) is used to link the branch to its corresponding delay slot in another block. If no page fault occurs, the delay slot executes and then jumps to the address in the register. For conditional branches that are not taken, the target address is the next instruction. This code is generated by the pagespan_assemble function.

Self-modifying code detection

Pages not containing code which has been compiled or where the code may have been modified since compilation are marked in the invalid_code array. Writes are checked against this array, and if a write hits a valid (compiled and unmodified) page, invalidate_block is called:

MIPS instruction: SW r1,8(r2)

ARM code:

ldr r3, [r11, #88] // pointer to invalid_code

add r4, r2, #8

cmp r4, #8388608

bvc handler

str r1, [r4]

ldrb r14, [r3, r4 lsr #12]

cmp r14, #1

bne invstub

In TLB mode, the invalid_code array is not checked directly. Instead, pages are marked non-writable in memory_map.

Compile options

ARMv5_ONLY

If this is defined, the UXTH instruction is not used, and the dynamic recompiler will generate literal pools instead of using movw/movt. This provides compatibility with older processors, but generates somewhat less efficient code.

RAM_OFFSET

When compiling for ARM, this allocates an additional register which is used to add an offset to all pointers to memory addresses between 0x80000000 and 0x807FFFFF. This allows the N64's memory to be mapped at an alternate address. This incurs a small performance penalty, but is required for certain operating systems (eg Google Android, which places shared libraries at 0x80000000).

This option is not used for x86. The x86 instruction set allows for a full 32-bit offset in the instruction encoding, making it unnecessary to allocate an additional register for this purpose.

CORTEX_A8_BRANCH_PREDICTION_HACK

If this is defined, the dynamic recompiler will avoid generating consecutive branch instructions without another instruction in between. This avoids a possible branch misprediction on the Cortex-A8 due to this processor having dual instruction decoders, but only one branch-prediction unit. See Assembly Code Optimization for details.

USE_MINI_HT

If this is defined, attempt to look up return addresses in a small hash table before checking the larger hash table. Usually improves performance.

IMM_PREFETCH

If this is defined, the x86 PREFETCH instruction is used to prefetch entries from the hash table. The increase in code size often outweighs the benefit of this.

REG_PREFETCH

Similar to the above, but loads the address into a register first, then uses the ARM PLD instruction. The increase in code size almost always outweighs the benefit of this.

R29_HACK

Assume that the stack pointer (r29) is always a valid memory address and do not check it. It is similar to the optimization described here. This can crash the emulator and is not enabled by default.

Debugging

Debugging information can be obtained by defining the assem_debug macro as printf. This will cause the dynamic recompiler to print debugging information to stdout. For each disassembled MIPS instruction, an entry similar to the following will be printed:

U: r1 r8 r11 r16 r31 UU: r29 32: r0 r9

pre: eax=-1 ecx=9 edx=-1 ebx=-1 ebp=29 esi=36 edi=-1

needs: ecx ebp esi r: r9

entry: eax=-1 ecx=9 edx=-1 ebx=-1 ebp=29 esi=36 edi=-1

dirty: ecx ebp esi

800001d8: LW r16,r29+14

eax=16 ecx=9 edx=-1 ebx=-1 ebp=29 esi=36 edi=-1 dirty: eax ecx ebp esi

32: r0 r9 r16

U: A list of MIPS registers which will not be used before they are overwritten (liveness analysis)

UU: A list of MIPS registers for which the upper 32 bits will not be used before they are overwritten

32: Registers that contain 32-bit sign-extended values

pre: The state of the register mapping prior to execution of this instruction. (-1 = no mapping; 36 = cycle count; The complete list of values with special meanings can be found in the source code)

needs: a list of register mappings that were considered necessary and which could not be eliminated to make room for other mappings

r: Registers that are known to contain 32-bit values and where optimizations rely on the assumption that the register does not contain a value outside of the range -231 to 231-1

entry: The minimum set of register mappings required to jump to this point

dirty: Cached registers that have been modified and will need to be written back

address: instruction - The decoded opcode, followed by the register mapping in effect after this instruction executes

An asterisk (*) designates locations which are the target of a branch instruction. Constant propagation will not be performed across these points.

After the complete disassembly, the recompiled native code is shown.

Note that the output can be quite voluminous; 20-30 MB is typical.

Potential improvements

Copy propagation/offset propagation

A common instruction sequence is of the form:

LUI r9,12340000

ADD r9,r9,r8

LW r9,5678(r9)

It would be helpful to recognize this as a load from r8+12345678. The current constant propagation code does not do so.

Unaligned memory access

A small improvement could be made by combining adjacent LWL/LWR instructions. The potential gain from doing so is very limited because these instructions typically represent less than 1% of all memory accesses.

SLT/branch merging

A frequent occurrence in MIPS code is an SLT or SLTI instruction followed by a branch. This is generated relatively inefficiently on x86 and ARM, first doing a compare and set, then testing this value and doing a conditional branch. Doing only one comparison would save at least one instruction, and could potentially save up to three instructions if the liveness analysis reveals that the result of the SLT instruction is used nowhere else.

While a potentially useful optimization, there are several problems with this approach. First, there are often additional instructions between the slt and the branch. These must be checked to make sure they do not modify the registers as that would prevent reordering the instruction stream as desired. Secondly, if the result of the slt is found to be live, but unmodified, on both paths of the branch, clean_registers will normally write this value before the branch, to avoid duplicating the writeback code on both paths of the branch. This optimization would have to be removed if the slt was combined with the branch.

x86-64

Currently the x86-64 backend generates only 32-bit instructions. Proper 64-bit code generation would improve performance.

PowerPC

It would be possible to add a PowerPC code generator to the dynamic recompiler. Currently no one is working on this. (The mupen64gc project is using a different codebase.)

The following is a summary of the changes which would be necessary to add a PowerPC backend.

The slt* instructions use conditional moves, which are unavailable on PowerPC. A suitable alternative (such as moves from the condition register) would need to be used.

The assembler can generate as much as 256K of code in a single block, however conditional branches on PowerPC are limited to +/-64K. It will be necessary to either restrict the block size, or insert jump tables in a manner similar to the literal pools on ARM.

PowerPC generally relies on early branch resolution rather than statistical branch prediction. Scheduling branch condition tests earlier may be advantageous. (For example, the address bounds check could be done in address_generation, rather than just before the load or store. Similarly it may be advantageous to test the branch condition and update the cycle count before executing the delay slot.)

MIPS

Recompiling MIPS into MIPS would be relatively straightforward, however the current code generator has no facility for filling delay slots. This capability would be required for efficient code generation.